When The War Ended, We All Wondered: What Should We Do Now!

Military Grade Burlap Sand Bags, Sand, Wood, Steel, Ropes and Mixed Media, 2021.

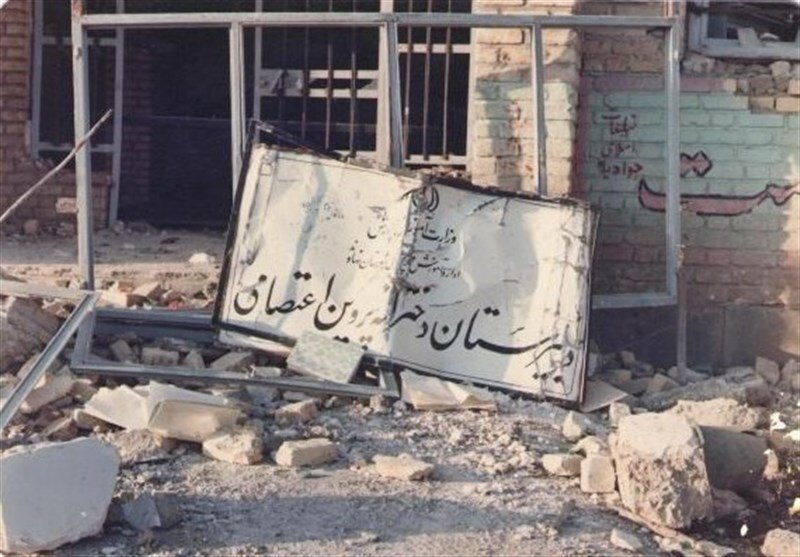

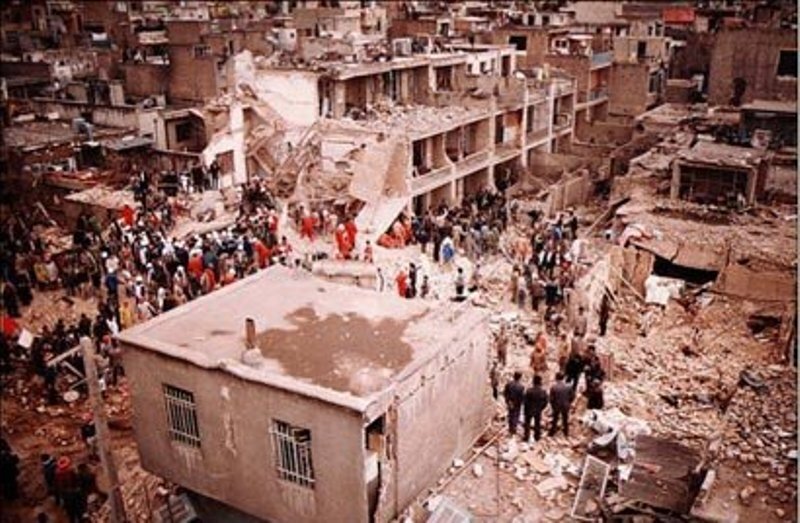

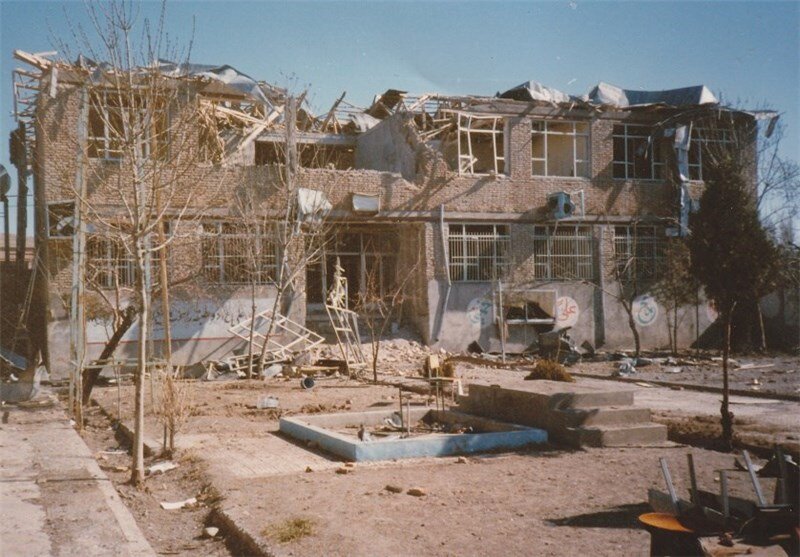

During the Iraq-Iran war, schools were commonly targeted by Iraqi bombs and missiles. Hence they started covering the inside walls with burlap sandbags. It was not even a surprise anymore to go to school and see some parts of the building had been bombed. While most of the time bombings were happening at night but they sometimes happened during the day and these bags in my case once saved our lives. The images above show the reality of that time, the third image of bombed schools is taken from the school next to my elementary school. What saved me was the burlap sandbags.

Below is how Christina Schmid describes the piece in her article.

“The white slanted surface dwarves our bodies. It dominates the space in a vaguely ominous way, an impression heightened by the circular glare of bright light emanating from below, projecting crosshairs on the ceiling. Sandbags are piled around the lower end of what resembles a giant cornhole board. The room-filling installation titled When the War Ended, We All Wondered What We Should Do Now! (2021) combines wood, steel, and burlap military-grade sandbags, and effectively collides cultural reference points and sensibilities. Cornhole, for those not blessed with midwestern childhoods, is a popular backyard game that involves setting up low, slanted boards and tossing small bags into a hole on the raised side of the board. Opposing teams take turns, and whoever tosses with the best aim and sinks the most bags, wins. Pedram Baldari, a Kurdish immigrant to the United States, remembers when he first encountered the game. His associations with the materials were far less pastoral: “We were in a room, maybe this big” —his gestures circumscribe the small gallery floor in front of the looming sculpture— “sixty kids and a teacher. No windows, just bodies crammed into the space. The walls were lined, the windows covered, with sandbags. That was my school room until fourth grade. Then the war ended. And all the teachers were saying, we need to get light in here! We need windows! We need air! All these kids are all eating hardboiled eggs… and you can imagine the smell.”

He laughs. Life under fire: a different childhood normal. The sculpture not only shifts the scale of the traditional game. The gestures involved in playing cornhole share an uncanny resemblance with how Baldari’s childhood teachers transformed the schoolhouse after the war ended: they invented a game to make the dismantling of the protective sandbag barriers fun. First, they instructed the students to dig a big hole in the schoolyard. Then, in the spirit of friendly contest, the kids threw as many sandbags as they could into the hole. The prize: a juice. The sculpture does not delve into the autobiographical but quietly lends an air of menace to the game: instead of colorful hand-sized sandbags, a stack of military grade burlap bags. The stark material choices distill into a discomfiting question: How far apart, how separate, is a wholesome game of cornhole from a sandbag-lined schoolhouse? How does a global regime of colonial capitalism, an economic system built on at times violent resource extraction far from home, enable one while necessitating the other? What happens to the ever-complicated notions of innocence, ignorance, and complicity here? The smooth white slanted surface does not reveal anything, but its massive presence, suspended, looms large, both precarious and intractable.”